Displaying items by tag: poetry

Super Blood Moon

Amarone moon

Dark fermented red

A couple whisper in the doorway

Before they go to bed

A fox stops in the arches

Glances at the moon and back

To the red eye of the signal

Hovering over the track

3.14 am 28 September 2015

A Poor Poet

You thought I was a poor poet

The first time that we met,

Upset to discover

The catastrophe of success

As soon as you walked in

You knew there was something wrong

Something has to give here

Someone

A poor poet has to lose it

Sell his soul for a song

Possessed and dispossessed

Before - to long

But what they never told you

Is you would pay the price

Abandoned so I could recover

My voice

For a poet is born

Of things that are not

From losses not from profits

And you were the cost.

You thought I was a poor poet

The first time that we met

Upset to discover

The catastrophe of success

You can't buy truth

You can't buy love

You can't buy this

But maybe you can earn it.

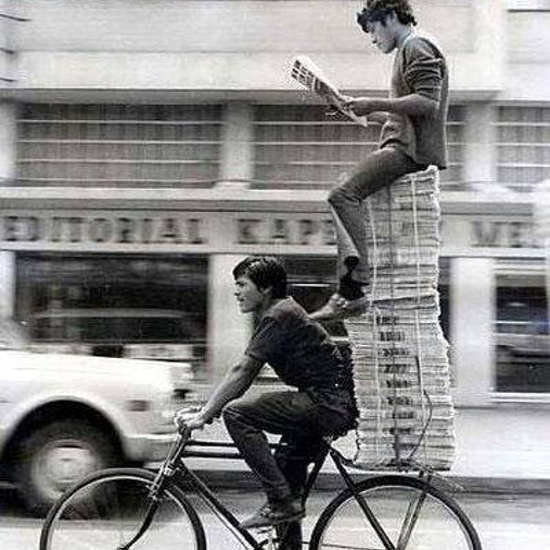

Stumbleupon Poetry Blog

This is shattered fragment of a stumbleupon blog, long since now defunct, where I used to store favourite images, and attach poems to them (or vice versa). Just goes to show that for all its claims of ubiquity, the digital domain doesn't give you much of a purchase in permanence.

PeterJukes's reviews

|

Together or Apart

Together

Or

Apart

Much easier to see

Just one dilemma

In the frame of forever

See it now

Together

Or

Apart

But unpick the words

Suspect the simplicity

Apart could be

Communing despite miles

A constant presence

Like a subtitle in your life

Apart could be

The meaning you hold

Like two strings vibrating

To the same note

Unpick the words

Together might mean

Cleaving down the middle

Inseparable as a wound

Dependent as enemies

Demanding as

A beggar's bowl

Imploring the pennies

That make you poor

Unpick the meaning, unpack the words

Go beyond the dilemma

See us both

Standing here

And listen to the world

Beneath the footsteps

And murmur of voices

And the passing cars

The world is so quiet

So quiet

And we have to keep

Ourselves

Together

And stop

Being

A part

Peter Jukes 1999

Farewell

And when I go

leave the window open

The boy is eating oranges

(I see him from my window)

The reaper is cutting down the corn

(I hear him from my window)

So when I go

leave the window open

Translated by Peter Jukes from Lorca's Despedida

Translated by Peter Jukes from Lorca's Despedida

In Step

And one time he was leading her through the darkness

And then another time she was leading him

The first time he reached out to touch her

She withdrew but searched and found his hand again

Towards the certainty of never

From the uncertainty of now

Through the certainty of pain

To the uncertainty of joy

Not Orpheus and his muse

But two lost children

Like Hansel and Gretel

Walking through the dark

Their hands only parting

Searching on the path

For whatever breadcrumbs

The birds might have ignored

Peter Jukes 1999

Spleen

I’m like the king of some rain swept terrain,

Rich but impotent, young yet ancient,

Detesting the fawning of his teachers,

Tired of his lap dogs and other creatures.

Nothing amuses him, hunting, falconry,

His people expiring in front of his balcony.

Even the jests of his favourite fool

Can't smooth the frown of this cruel recluse.

His petal-strewn bed has become a tomb,

And his handmaidens, made to make princes swoon,

Can't find outfits scandalous enough

To raise a flicker from his immaculate corpse.

The alchemist who transmutes gold from lead

Fails to draw from him that poisonous element.

And those baths of blood the Romans conceived,

To give decrepit tyrants some relief...

Can't even stir the veins in this lethargic flesh

In which the green sludge of Lethe runs instead.

Translated by Peter Jukes from Spleen by Charles Baudelaire

Lorca and Duende

From Theory and Function of Duende

Once, the Andalusian ‘Flamenco singer’ Pastora Pavon, La Niña de Los Peines, sombre Spanish genius, equal in power of fancy to Goya or Rafael el Gallo, was singing in a little tavern in Cadiz. She played with her voice of shadows, with her voice of beaten tin, with her mossy voice, she tangled it in her hair, or soaked it in manzanilla or abandoned it to dark distant briars. But, there was nothing there: it was useless. The audience remained silent.

Once, the Andalusian ‘Flamenco singer’ Pastora Pavon, La Niña de Los Peines, sombre Spanish genius, equal in power of fancy to Goya or Rafael el Gallo, was singing in a little tavern in Cadiz. She played with her voice of shadows, with her voice of beaten tin, with her mossy voice, she tangled it in her hair, or soaked it in manzanilla or abandoned it to dark distant briars. But, there was nothing there: it was useless. The audience remained silent.

In the room was Ignacio Espeleta, handsome as a Roman tortoise, who was once asked: ‘Why don’t you work?’ and who replied with a smile worthy of Argantonius: ‘How should I work, if I’m from Cadiz?’

In the room was Elvira, fiery aristocrat, whore from Seville, descended in line from Soledad Vargos, who in ’30 didn’t wish to marry with a Rothschild, because he wasn’t her equal in blood. In the room were the Floridas, whom people think are butchers, but who in reality are millennial priests who still sacrifice bulls to Geryon, and in the corner was that formidable breeder of bulls, Don Pablo Murube, with the look of a Cretan mask. Pastora Pavon finished her song in silence. Only, a little man, one of those dancing midgets who leap up suddenly from behind brandy bottles, sarcastically, in a very soft voice, said: ‘Viva, Paris!’ as if to say: ‘Here ability is not important, nor technique, nor skill. What matters here is something other.’

Then La Niña de Los Peines got up like a madwoman, trembling like a medieval mourner, and drank, in one gulp, a huge glass of fiery spirits, and began to sing with a scorched throat, without voice, breath, colour, but…with duende. She managed to tear down the scaffolding of the song, but allow through a furious, burning duende, friend to those winds heavy with sand, that make listeners tear at their clothes with the same rhythm as the Negroes of the Antilles in their rite, huddled before the statue of Santa Bárbara.

La Niña de Los Peines had to tear apart her voice, because she knew experts were listening, who demanded not form but the marrow of form, pure music with a body lean enough to float on air. She had to rob herself of skill and safety: that is to say, banish her Muse, and be helpless, so her duende might come, and deign to struggle with her at close quarters...

Lorca translation's on this site

Why Must I Write?

Paris, February 17, 1903

Dear Sir,

Your letter arrived just a few days ago. I want to thank you for the great confidence you have placed in me. That is all I can do. I cannot discuss your verses; for any attempt at criticism would be foreign to me. Nothing touches a work of art so little as words of criticism : they always result in more or less fortunate misunderstandings. Things aren't all so tangible and sayable as people would usually have us believe; most experiences are unsayable, they happen in a space that no word has ever entered, and more unsayable than all other things are works of art, those mysterious existences, whose life endures beside our own small, transitory life.

With this note as a preface, may I just tell you that your verses have no style of their own, although they do have silent and hidden beginnings of something personal. I feel this most clearly in the last poem, "My Soul." There, something of your own is trying to become word and melody. And in the lovely poem "To Leopardi" a kind of kinship with that great, solitary figure does perhaps appear. Nevertheless, the poems are not yet anything in themselves, not yet anything independent, even the last one and the one to Leopardi. Your kind letter, which accompanied them, managed to make clear to me various faults that I felt in reading your verses, though I am not able to name them specifically.

You ask whether your verses are any good. You ask me. You have asked others before this. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you are upset when certain editors reject your work. Now (since you have said you want my advice) I beg you to stop doing that sort of thing. You are looking outside, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you - no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write.

This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out in assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple "I must," then build your life in accordance with this necessity; your while life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse. Then come close to Nature. Then, as if no one had ever tried before, try to say what you see and feel and love and lose. Don't write love poems; avoid those forms that are too facile and ordinary: they are the hardest to work with, and it takes great, fully ripened power to create something individual where good, even glorious, traditions exist in abundance. So rescue yourself from these general themes and write about what your everyday life offers you; describe your sorrows and desires, the thoughts that pass through your mind and your belief in some kind of beauty - describe all these with heartfelt, silent, humble sincerity and, when you express yourself, use the Things around you, the images from your dreams, and the objects that you remember.

If your everyday life seems poor, don't blame it; blame yourself; admit to yourself that you are not enough of a poet to call forth its riches; because for the creator there is not poverty and no poor, indifferent place. And even if you found yourself in some prison, whose walls let in none of the world's sounds - wouldn't you still have your childhood, that jewel beyond all price, that treasure house of memories? Turn your attentions to it. Try to raise up the sunken feelings of this enormous past; your personality will grow stronger, your solitude will expand and become a place where you can live in the twilight, where the noise of other people passes by, far in the distance. - And if out of this turning-within, out of this immersion in your own world, poems come, then you will not think of asking anyone whether they are good or not. Nor will you try to interest magazines in these works: for you will see them as your dear natural possession, a piece of your life, a voice from it. A work of art is good if it has arisen out of necessity. That is the only way one can judge it. So, dear Sir, I can't give you any advice but this: to go into yourself and see how deep the place is from which your life flows; at its source you will find the answer to the question whether you must create. Accept that answer, just as it is given to you, without trying to interpret it. Perhaps you will discover that you are called to be an artist. Then take the destiny upon yourself, and bear it, its burden and its greatness, without ever asking what reward might come from outside. For the creator must be a world for himself and must find everything in himself and in Nature, to whom his whole life is devoted.

But after this descent into yourself and into your solitude, perhaps you will have to renounce becoming a poet (if, as I have said, one feels one could live without writing, then one shouldn't write at all). Nevertheless, even then, this self-searching that I as of you will not have been for nothing. Your life will still find its own paths from there, and that they may be good, rich, and wide is what I wish for you, more than I can say

What else can I tell you? It seems to me that everything has its proper emphasis; and finally I want to add just one more bit of advice: to keep growing, silently and earnestly, through your while development; you couldn't disturb it any more violently than by looking outside and waiting for outside answers to question that only your innermost feeling, in your quietest hour, can perhaps answer.

It was a pleasure for me to find in your letter the name of Professor Horacek; I have great reverence for that kind, learned man, and a gratitude that has lasted through the years. Will you please tell him how I feel; it is very good of him to still think of me, and I appreciate it.

The poems that you entrusted me with I am sending back to you. And I thank you once more for your questions and sincere trust, of which, by answering as honestly as I can, I have tried to make myself a little worthier than I, as a stranger, really am.

Yours very truly,

Rainer Maria Rilke

Selected Poems 1976-2006

Below Stolen Moments

|